As children learn to express themselves verbally and think more abstractly, they rely less and less on visual memory. Given that the ability invariably disappears by age 12, Haber theorized that in the absence of sophisticated language skills, young children depend more on visual imagery for memory processing. Indeed, such children’s ability to accurately describe an eidetic image is no better than children describing the same scene purely from memory, indicating that, like all memory, the process is reconstructive, more like painting a picture than taking a photograph. However, these images typically fade from view within a minute or two, and are hardly the hyper-accurate recordings implied by the term photographic memory.

#PHOTOGRAPHIC MEMORY VS EIDETIC SERIES#

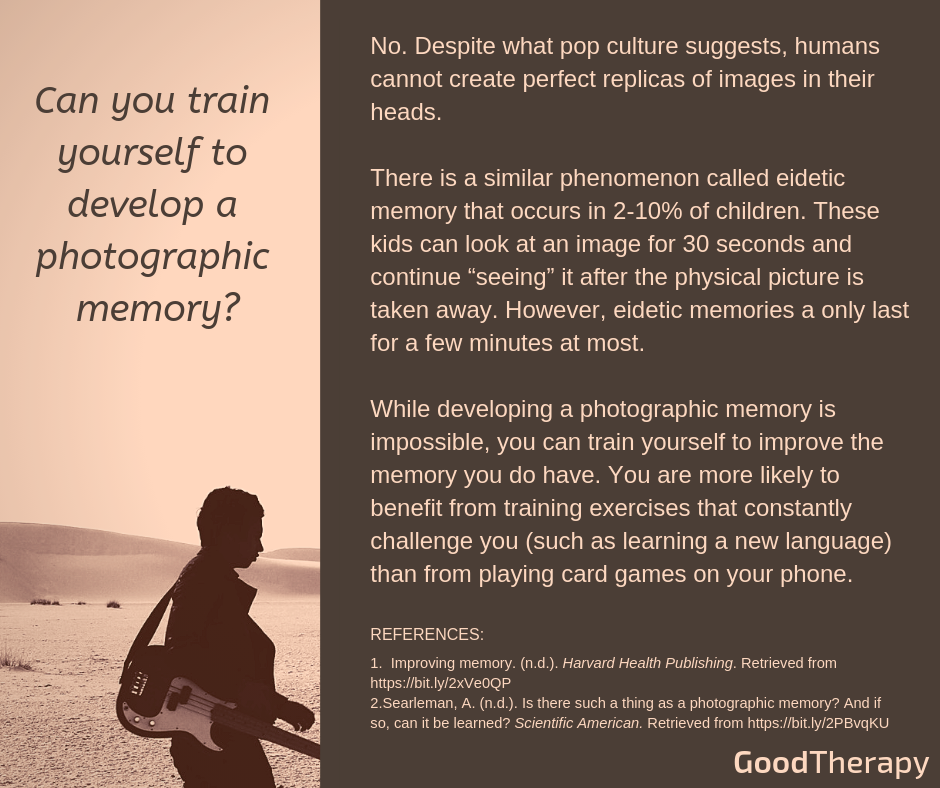

In a series of experiments conducted in the late 1970s, Haber determined that around 2-10% of primary school-aged children possess the ability to retain a clear afterimage in their visual field. “…hold a visual image in their mind with such clarity that they can describe it perfectly or almost perfectly … just as we can describe the details of a painting immediately in front of us with near perfect accuracy.”Īccording to leading expert on the subject Ralph Norman Haber, this ability is found almost exclusively in children aged 6-10 – and only a very small percentage at that.

According to Scott Lilienfeld, professor of psychology at Emory University, Eidetic memory, from the Greek eidos, or “visible form, ” refers to a person’s ability to: It is important to note here that while the terms photographic and eidetic memory are often used interchangeably, they are, in fact, two distinct phenomena. In fact, as far as most psychologists and neurologists are concerned, it might not even exist at all. But while the idea of photographic memory is widespread in popular culture, the scientific reality of the phenomenon is rather different from how it is commonly depicted. Throughout history, many people have claimed to have this extraordinary gift – typically in the form of being able to instantly memorize large volumes of text – from scientists Nikola Tesla and John von Neumann to writer Truman Capote to Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos and even Mister T. The case of Solomon Shereshevsky is one of the most famous and oft-cited examples of what is commonly known as photographic or eidetic memory – the ability to retain information as clearly and accurately as taking a photograph. “I simply had to admit that the capacity of his memory had no distinct limits. In The Mind of a Mnemonist, his classic 1968 case study on Shereshevsky, Luria wrote: Even more astonishing, he seemed able to retain this information in perpetuity years later he could still recite the strings of numbers Luria had given him – forwards and backwards. Whatever Luria threw at him – long strings or matrices of numbers, lengthy speeches, and even poems in foreign languages he neither read nor spoke, Shereshevsky was able to memorize with perfect accuracy in mere minutes. Over the next 15 years, Luria would subject Shereshevsky – identified in his writings only as “S” – to a series of increasingly elaborate memory tasks, all of which his subject defeated with almost supernatural ease. Several days later, Shereshevsky duly presented himself at the Academy of Communist Education, where he was introduced to up-and-coming neurologist Alexander Luria. Astonished and sensing a good story, the editor suggested Shereshevsky have his memory scientific ally measured. Then, before the editor could argue, Shereshevsky proceeded to recite the entire meeting down to the last detail.

The editor pulled the reporter aside to question him, only for the man, one Solomon Shereshevsky, to reveal that he never took notes because he had a perfect memory. One day in April 1929, a Moscow newspaper editor was handing out assignments when he noticed that one of his reporters wasn’t taking any notes.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)